Textiles conducive for flexible, wearable electronic devices

A team of researchers from the State University of New York (SUNY), popularly called the Binghamton University, have developed a flexible and stretchable bio-battery powered by bacteria from fabric. The bio-battery has the potential to reform the future of wearable electronics and smart textiles. Lead researcher Prof Seokheun (Sean) Choi from the university's department of electrical & computer engineering talks to Fibre2Fashion about the need for flexible batteries and explains the potential of textile-based, bacteria-powered bio-battery.

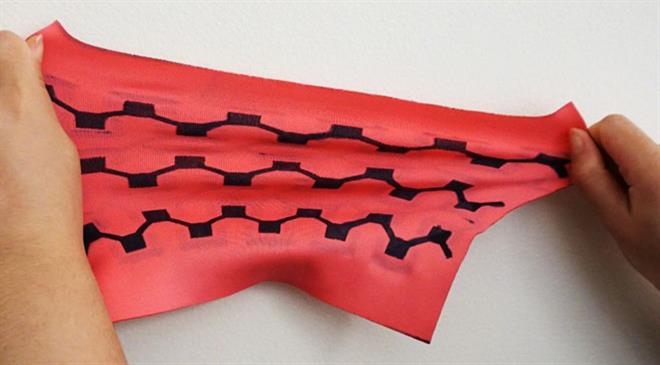

We used a fabric comprising 92 per cent polyester and 8 per cent spandex. We selected this fabric because it was stretchable enough for the mechanical deformation tests and hydrophilic enough for the storage of the bacteria-containing liquid. Conductive textiles are required to extract electrons from the microorganisms, and at the same time, the textiles must have open pores and hydrophilic features to adsorb the cells in liquid while the device needs to be mechanically flexible, stretchable and easily integratable with other necessary electronic components.

With the rapid evolution of wireless sensor networks for the emerging Internet-of-Things (IoT), there is a clear and pressing need for flexible and stretchable electronics that can be easily integrated with a wide range of surroundings to collect real-time information. Those electronics must perform reliably even while closely - even intimately when used on humans - attached while deformed toward complex and curvilinear shapes. To achieve the standalone and sustainable operation of the sensor networks, we considered a flexible, stretchable, miniaturised bio-battery as a truly useful energy technology because of their sustainable, renewable and eco-friendly capabilities. For the long-term goal, other wearable electronics, such as activity trackers, socks and gloves, can be powered as well.

It is hard to say at this moment because this work is in the infant stage.

Most microorganisms use respiration to convert biochemical energy stored in organic matter into biological energy, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), where this process involves a cascade of reactions through a system of electron-carrier biomolecules in which electrons are transferred to the terminal electron acceptor. Most forms of respiration use a soluble compound as an electron acceptor, such as oxygen, nitrate and sulfate; however, some microorganisms are able to respire solid electron acceptors to obtain biological energy. These microorganisms can transfer electrons produced via metabolism across the cell membrane to an external electrode. MFCs typically comprise anodic and cathodic chambers separated by a proton exchange membrane (PEM) so that only H+ or other cations can pass from the anode to the cathode. A conductive load connects the two electrodes to complete the external circuit.

The device generated a maximum power of 6.4µW/cm2 and current density of 52µA/cm2, which are similar to other flexible paper-based MFCs.

This work gained significant attention from the community and was reported by many media outlets, including ScienceDaily, Newswise, Techxplore and EurekAlert.

First, the power needs to be improved significantly for the future applications. Second, we will demonstrate that sweat generated from the human body can be a potential fuel to support bacterial viability, providing the long-term operation of the MFCs.

Compared to traditional batteries and other enzymatic fuel cells, the MFCs can be the most suitable power source for wearable electronics because the whole microbial cells as a biocatalyst provide stable enzymatic reactions and long life time. Sweat generated from the human body can be a potential fuel to support bacterial viability, providing the long-term operation of the MFCs.

The organic fuel for microorganisms can be any type of biodegradable substrate, including wastewater, soiled water from a puddle, and biological/physiological fluids, such as tears, urine, blood and sweat.

Yes. Flexible electronics are getting more and more attention these days because of the wide application possibilities. However, we have tended to overlook the importance of flexible energy supplying devices even though they are necessary for a truly stand-alone device platform. My stretchable and twistable power device printed directly onto a single textile substrate can establish a standardised platform for flexible bio-batteries and will be potentially integrated into wearable electronics in the future.

Smart wearables will attract greater attention because of their continuous interaction with the human body, such as monitoring blood pressure, heart rate, motion, biomarkers in sweat, and other health-related conditions. Furthermore, smart wearables will enable a next-generation of smart, stand-alone, always-on wireless sensor networks designed to collect real-time information for human safety and security. (HO)

DISCLAIMER: All views and opinions expressed in this column are solely of the interviewee, and they do not reflect in any way the opinion of technicaltextile.net.