Spiders use their silk to catch lunch. Now physicists are using it to catch light. New research shows that natural silk could be an eco-friendly alternative to more traditional ways of manipulating light, such as through glass or plastic fiber optic cables.

Biomedical engineer Fiorenzo Omenetto of Tufts University in Boston will discuss his group's work fabricating concoctions of proteins that make use of silk's optical properties for implantable sensors and other biology-technology interfaces.

By integrating real spider silk into a microchip, the researchers found that silk could not only propagate light but could also direct light, or "couple" it, to selected parts of the chip. Huby hopes #

Physicist Nolwenn Huby at the CNRS Institut de Physiques de Rennes in France will talk about her team's use of pristine, natural spider silk to guide light through photonic chips—technology that could give birth to silk-based biosensors and medical imaging devices for use inside the body.

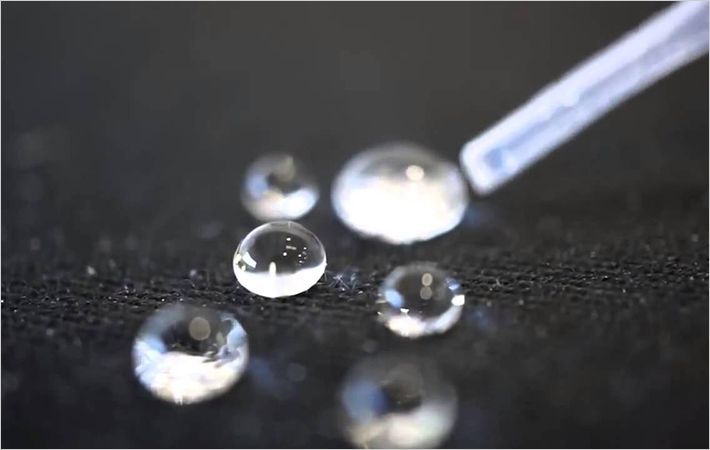

Both groups hope their work will lead to medical advancements that take advantage of the optical properties of silk. One of the strongest fibers in nature (the dragline used by spiders to form the structure of their webs is stronger, pound for pound, than steel), silk is biocompatible, biodegradable, and extremely hardy. Produced naturally by spiders and silkworms, it is a renewable resource. Added to these benefits is the more recent discovery that silk is a gifted manipulator of light, which can travel through silk almost as easily as it flows through glass fibers.

Though it may not be the best material in every one of these categories, the combination of talents is what makes silk such an attractive material to study, Omenetto explains. "There are materials that can do one of each, or a few of each," he says, "but seldom all of each."

In their efforts to exploit silk's optical merits, Omenetto's team is developing silk-based materials that look like plastic, but retain the optical properties of pristine silk. One of the advantages of these materials is that they can degrade and be reabsorbed by the body. A sensor or tag made of silk protein could be implanted—at the site of a fractured bone, for example, to monitor healing—and merely left to dissolve. Once its purpose had been served, the silk tag would harmlessly fade away.

Omenetto is currently investigating a range of questions, from fundamental to commercial, and they go beyond implantable optics. His team recently won an INSPIRE grant from the National Science Foundation to create electronic components that are compostable. He has developed and tested a blue laser made from silk fiber-doped materials that is not only biodegradable but also uses less power to induce lasing than the acrylic materials that are commonly used. He is also exploring the possibilities of using silk to integrate a technological component with living tissue. "We're thinking of how to scale up [production], how to interface with current technology," Omenetto says. He hopes some of the more "gadget-like" fruits of his labor will be commercially available within the next five to 10 years.

Silk-doped composites are the subject of Omenetto's talk at FiO, but the optical merits of pristine silk will be the subject of Huby's. Her team is experimenting with pure spider silk as a relatively inexpensive and ecologically friendly way to manipulate light within photonic chips.

As a light guide, silk works in a way comparable to the more commonly used glass microfibers that carry light within a chip; but silk comes out of the spider ready to use, whereas glass microfibers have to be heated to high levels and carefully sculpted at great expense. Huby's silk is collected by a group of molecular spectroscopy experts led by Michel Pézolet of Université Laval in Quebec, then integrated into circuits at her team's lab at Rennes. To her knowledge, this is the first time the optical properties of pristine silk have been exploited.